Crates and Chipboard as Context

Artist Hew Locke's exhibition at the British Museum challenges the institution's collection through on-the-nose exhibition design and conversational commentary.

For a five-month period last Winter, a small semi-circular gallery on the upper floor of the British Museum provided a viewing experience that contrasted sharply with what you'd find in the rest of the building: cases crowded with artefacts but short on stories. Instead, what have we here?, Hew Locke's solo-show-cum-collection-display did just as much telling as showing, in its exploration of the connections between British imperialism and the museum's holdings.

THE WORK

The show featured works by Locke (who happens to be one of my favourite contemporary artists) alongside selected objects from the British Museum's collection, organised under the themes of 'sovereigns', 'trade', 'conflict', and 'treasure'.

Locke's artworks often appropriate and recontextualise colonial documents or statues. For example, in his Share series of works, Locke paints on original stock certificates for companies that extracted wealth via colonialism. And, in his Souvenir series, Locke loads up busts of British royals with found materials symbolising empire.

Works from these two series (amongst others) were set in dialogue with artefacts with dark histories: 18th century pro-slavery propaganda, drawings and watercolours made on plantations or of indigenous cultures, and precious pieces looted during military expeditions.

THE WOW FACTORS

Curated by Locke with support from curators Indra Khanna and the British Museum's Isabel Seligman, what have we here? is pointedly personal. No exhibition at this particular institution can be neutral (I'm of the firm opinion that saying nothing about an object's provenance is still saying something), and this one doesn't pretend to be. It makes its point of view clear from the moment you walk in, and reiterates it till you walk out. Here are a few ways how:

(1) Damning Displays

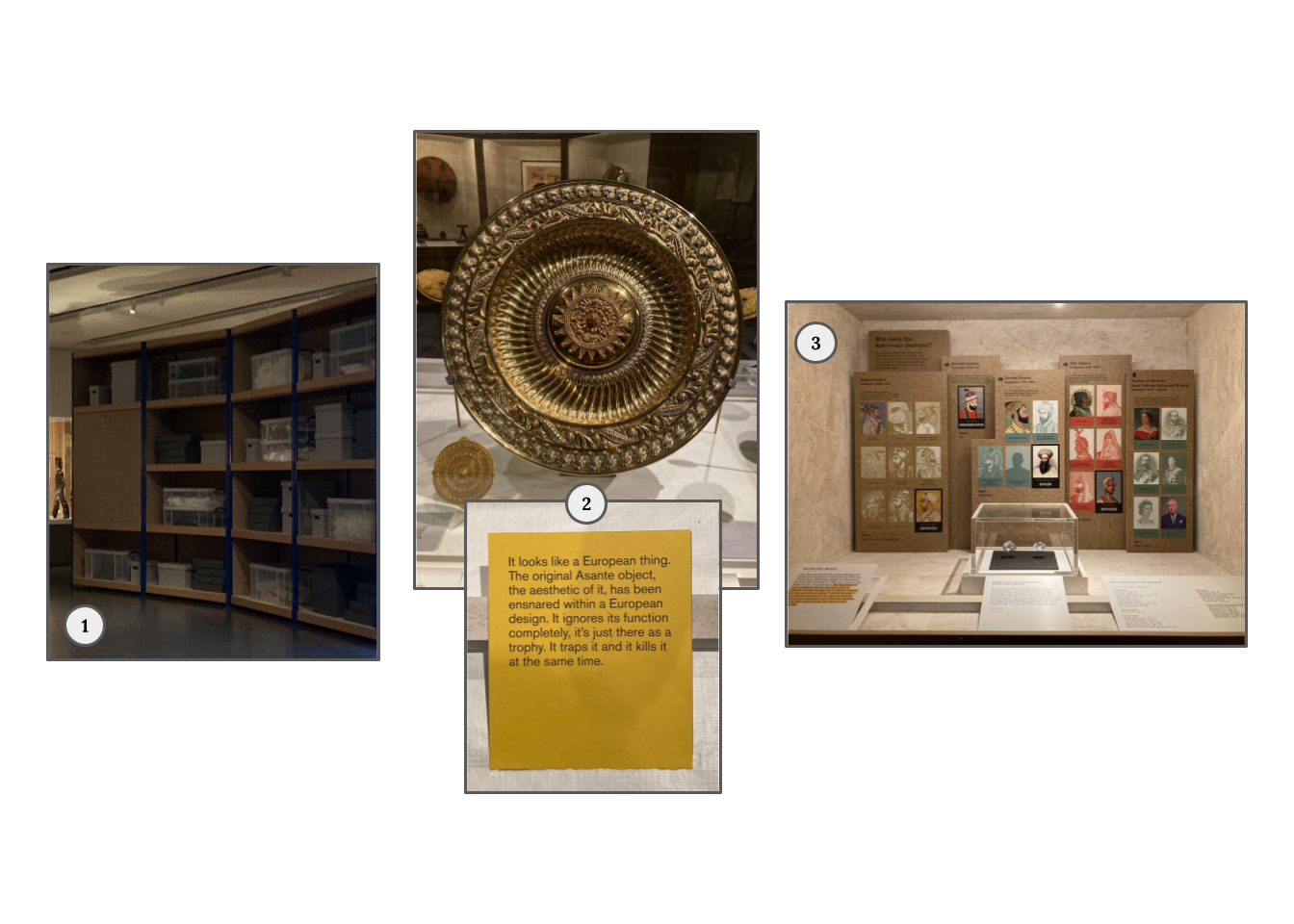

There is nothing subtle about the design of this exhibition—and that’s a good thing. The gallery you enter feels like a storage closet where objects are still being unpacked. Works are displayed in shipping crates, some stacked to the ceiling. You're immediately reminded (or informed) of how many of items on show arrived to this place from far-flung corners of the globe.

(2) Context and Commentary

In this show, the artist's perspective is ever-present, included alongside the classic context cards showing information about the who, what, and where of an item. Little speakers dangling from the ceiling and a video at the start literally bring Locke's voice into the gallery (listen to one audio clip looped overhead below) and bright yellow cards feature quotes providing his personal observations or reasons for including a piece as part of the curation.

(3) Space for the Story

Unlike in the rest of this museum where priceless treasures are crammed together in vitrines with a maze of museum labels to navigate if you want any information, the artefacts in Hew Locke's curation are carefully contextualised. Not just by the conversational commentary (mentioned just above), but through detailed context cards and even infographics if necessary.

For example, replicas of the Koh-i-Noor diamond are accompanied by an illustrated overview of all the rulers who ever owned the diamond (those from South-Asia, and then the British Royals who ended up with it), laying out a much broader and more detailed history of the stone than I’ve typically seen.

"If you don't like a good story, this show ain't for you" — Hew Locke

Immediately after seeing the show, I wandered over to Room 25 on the lower floor: the British Museum’s ‘Africa’ gallery. There, several original Benin bronzes (replicas of which had been included and explained in Locke’s show) sat in dusty glass vitrines, looking magnificent, but lacking the context and story that helps people understand their value (and current status as contested objects).

Hew Locke: what have we here? was on view at the British Museum in London between October 2024 and February 2025. If you missed the exhibition but would like to learn more, I suggest watching this recording of a curator’s tour, or purchasing the catalog.